In the state of Maharashtra, which ranks as the second most urbanized state in India after Tamil Nadu, the situation in Vidarbha stands out. Historically known for its semi-arid climate, this region has long struggled with high temperatures and acute water scarcity. The region has been home to major coal-based power plants, food, agro-processing, and cotton industry, amongst others. As urbanization accelerates in cities and towns in the Vidarbha region, especially cities like Amravati and Akola, the problem is intensifying. Amongst the tier 2 cities in the Vidarbha region, Amravati has the highest population (Census, 2011).

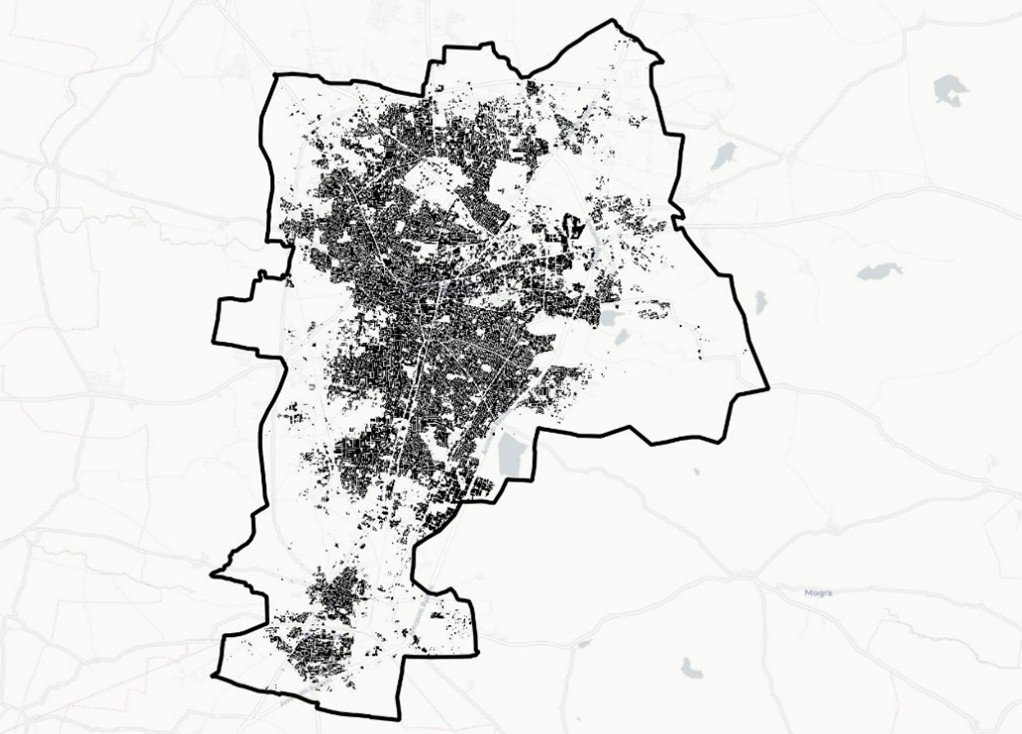

Amravati, historically an agricultural hub, is transforming into a thriving urban center. Located in eastern Maharashtra, the city serves as a commercial and administrative hub. From a population of 647,057 in 2011, Amravati is now estimated to have 917,000 residents in 2024, a 41% increase. Rapid infrastructure development is fueling this urban shift, making the city increasingly attractive to businesses, industries, and migrants. Figure 1 map shows that there is a rise in development beyond the city center. The city’s growth is also being spurred by state-level initiatives, such as the Mumbai Nagpur Expressway launched in 2022, which has connected Vidarbha region with Maharashtra’s major industrial centers. This project is expected to bring more industries to the city, creating jobs and boosting its economic profile. Additionally, Amravati is positioned as a key player in the Smart Cities Mission, a national initiative that focuses on improving urban infrastructure, sustainability, and technology.

Source: Map Data from EOC Geoservice; Visualisation by Author

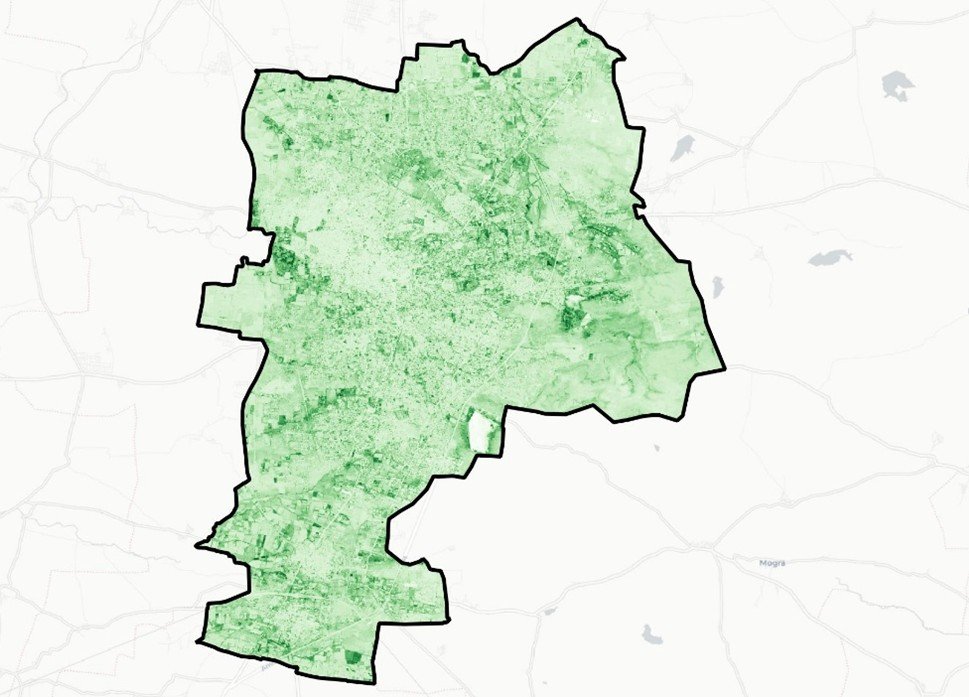

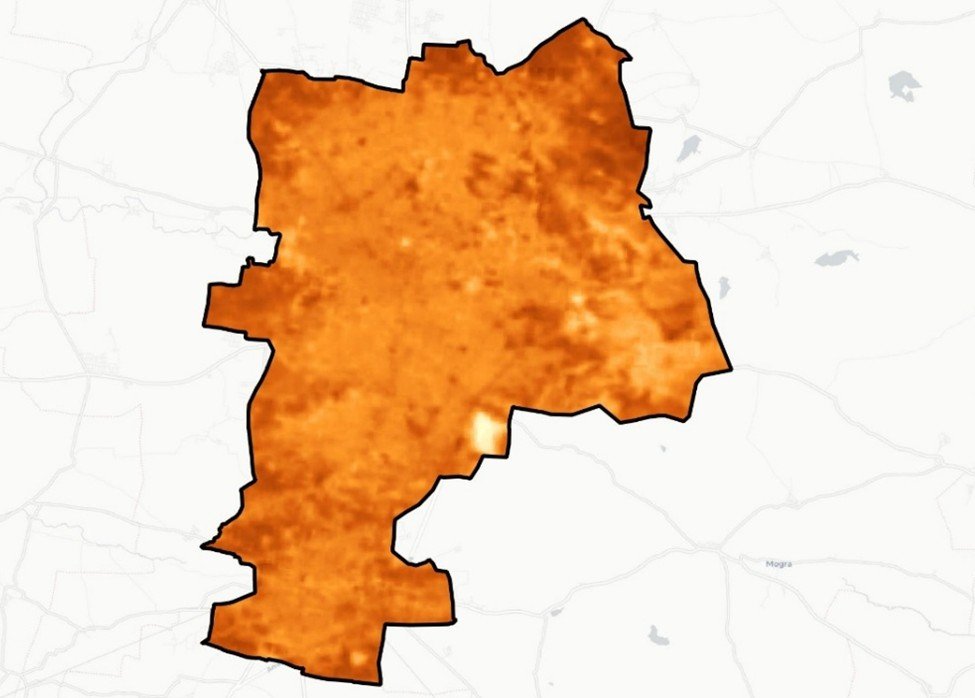

This city, once relatively small, is experiencing surging populations, with infrastructure often unable to keep pace. Haphazard urban growth, characterized by unplanned construction, poorly regulated land use, and inefficient urban designs only worsens the situation, contributing to higher temperatures and exacerbating the urban heat island (UHI). The urban heat island effect occurs when built-up areas, lacking adequate green spaces, absorb and retain heat more than their rural counterparts. Figure 2 shows the vegetation spread in the city, when compared with the temperature map (Figure 3), it is evident that places with moderate vegetation have lower temperature. The vegetation map shows that the city lacks moderate and dense vegetation which leads to increased temperatures. The rise in temperature not only makes daily life more uncomfortable but also increases energy consumption, health risks, and economic costs.

Source: European Space Agency, 2020, “Normalized Difference Vegetation

Index”.; Visualisation by Author

Source: Map Data from Landsat Level 2 Surface Temperature Science Product courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey; Visualisation by Author

While this problem is widespread across many rapidly growing cities in India, there are concrete steps that can be taken to mitigate these risks. One of the most promising approaches is the development of heat action plans. Heat action plans are comprehensive, data-driven strategies designed to reduce the impact of heat waves on urban populations. India has taken steps towards developing heat action plans at national, state and city level. They typically include early warning systems, cooling centers, public health infrastructure, and urban planning measures aimed at increasing green space and reducing the heat-absorbing surfaces in the built environment. One of the most notable examples of a successful heat action plan is Ahmedabad, Gujarat, which implemented a heat action plan in 2013. A 2018 study evaluated the effectiveness of the Ahmedabad HAP before and after implementation. The study found that an estimated 2,380 deaths were avoided in the post-HAP period. The findings suggest that the Ahmedabad HAP protected health against mortality associated with extreme heat. (Gujarat State Action Plan 2020). The Cool roof program has been an innovative and successful solution, especially for the vulnerable population of the city. The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation and knowledge partners have conducted several cool roof pilot programs, including pilots in 2017 and 2018, applying white lime wash to 3,000 low-income homes in the city, with 500 in each city zone, covering almost 2% of the city’s low-income households (Ahmedabad Heat Action plan Update Report, 2019). Ahmedabad not only strengthened the existing healthcare facilities, but also introduced mobile health units that can provide emergency healthcare services, including the treatment of heat stress, in the event of heatwaves. These mobile units are equipped with cooling systems and can be deployed to high-risk areas or communities that lack direct access to healthcare.

Incremental actions such as water kiosks in public spaces and public awareness campaigns on heat impacts, while essential, often preserve the status quo, and need to be complemented with transformational, system-wide agendas such as targeted implementation of heat-resilient building codes or a better articulation of how cities can balance grey-green-blue infrastructure solutions (IIHS,2024). While modern problems require modern solutions, Amravati should consider adapting its traditional building techniques for heat mitigation, as these methods were specifically designed to cope with the region’s extreme temperatures and climatic conditions. The use of mud and cow dung plaster in walls, for instance, provides natural insulation that helps maintain cooler indoor temperatures during the scorching summer months, while the thick, insulated walls of traditional homes offer thermal stability. Additionally, the open courtyard layout and use of ventilation techniques ensured better airflow, minimizing the need for mechanical cooling.

Source: Maharashtra Tourism

In addition to the typical inclusions of the heat action plan, implementing traditional heat mitigation techniques in Vidarbha region requires a multi-faceted approach. The Municipal councils need to develop building codes and guidelines that shall promote the use of natural insulation, ventilation, and cooling systems based on traditional techniques. The development plans and bye-laws should incorporate modern housing layouts inspired by traditional courtyards and open spaces. Incorporating traditional water management systems such as step wells, ponds, and water harvesting systems into urban landscapes can further reduce the temperature. The evaporation of water from these features can provide cooling effects in the surrounding areas.

Governments at the local, state, and national levels can offer subsidies or tax incentives for buildings that use sustainable materials and heat mitigation techniques. This could help reduce the financial burden of using these techniques, especially for low-income families. By combining the knowledge of ancient building methods with modern technology and governance support, Amravati can become a model for climate-resilient, energy-efficient housing. This would not only help reduce the urban heat island effect but also conserve local resources, revitalize local traditions, and improve the overall quality of life for residents.

Amravati’s journey from a small agricultural hub to a rapidly growing urban center offers both a challenge and an opportunity. As the city continues to expand, it must prioritize addressing the escalating risks of heat waves and the urban heat island effect through a combination of innovative, data-driven strategies and the revival of traditional cooling techniques. By incorporating sustainable building practices, improving urban infrastructure, and promoting water conservation, Amravati has the potential to not only safeguard the health and well-being of its residents but also lead the way for other tier-2 cities facing similar challenges. The success of Amravati in mitigating heat-related impacts could serve as a powerful model for cities across India, proving that climate resilience is not just a necessity but an opportunity for sustainable urban growth.

Bibliography

World Urbanisation Prospects Report, United Nations, 2014

Ahmedabad Action Plan Update Report, 2019

Gujarat State Action Plan, 2020

https://www.census2011.co.in/data/town/802690-amravati-maharashtra.html

https://www.census2011.co.in/census/city/348-akola.html#google_vignette

https://www.mohua.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/11MaharashtraAmravati02-csmc008.pdf

https://www.nature.com/articles/s44284-024-00074-0

Data Sources

DLR. 2019. “World Settlement Footprint – Sentinel-1/2 – Global”. Earth Observation Center Geoservice.

ESA 2017 Land Cover CCI Product User Guide Version 2. Tech. Rep. Retrieved February 24, 2020 from

http://maps.elie.ucl.ac.be/CCI/viewer/download/ESACCI-LC-Ph2-PUGv2_2.0.pdf

European Space Agency. 2020. “Normalized Difference Vegetation Index”. Sentinel-2. https://scihub.copernicus.eu/dhus/